The Once Upon a Time in China franchise is regularly cited as having kickstarted the weirdly dormant martial arts film genre in the Asian market, but it's also arguable that the series helped to foster another element of "eastern" cinema that is not necessarily relegated only to China (Korean films also come to mind in this regard): a kind of "rah rah" jingoism that seeks to exploit national identity while also perhaps hinting, none too subliminally at times, that the "natives" (Chinese or otherwise) may be just a bit smarter than some of the interlopers.

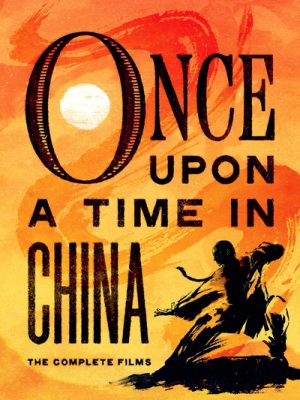

Tsui Hark's fingerprints are all over the five entries in the Once Upon a Time in China series. Tsui produced and co-wrote all the films in the series, and directed four of them. Though each can be enjoyed according to its own merits, taken together the series traces out a very specific arc both in terms of historical era and character development. Turn-of-20th-century period pieces, replete with absurdly over-the-top kung fu (not to mention wire fu) set pieces, and characterized by a broad streak of antic comedy, these films are both crowd-pleasers and sly reinterpretations of episodes in Chinese history.

The films, which were released between 1991 and 1994, focus on martial arts master and traditional Chinese medicine practitioner Wong Fei-hung, played by Jet Li in the first three installments and Vincent Zhao in the last two. Wong is a figure drawn from real life, who had been depicted previously in dozens of films and television programs as a venerable old man, so Li's younger, more dynamic portrayal is part and parcel of Tsui's tendency toward unconventional recontextualizations. The series's frequent inclusion of historical figures does double duty as both a comment on a particular moment in Chinese history as well as sociopolitical aspects of contemporary Hong Kong in the leadup to its 1997 handover to China.

The series plays out the often contentious, tendentious relationship between China and the West. On one level, this is embodied at the interpersonal level through the burgeoning romance between Wong and his so-called 13th Aunt (Rosamund Kwan), who returns to town dressed in Victorian garb, fluent in English, and with a newfangled box camera in tow. In the third film, she receives an early movie camera and, in a nifty bit of self-reflexivity, some footage that she shoots is integral to exposing a murderous conspiracy. In this formulation, Wong represents a dogged traditionalism, while 13th Aunt stands for measured assimilation.

Read more / Download movie Originally published at MovieWorld.ws

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий